Rise and Fall of the Knights Templar (Part II)

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

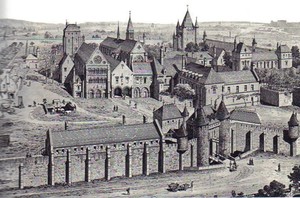

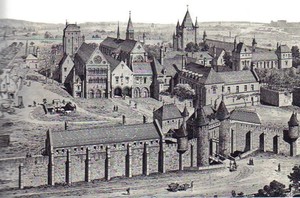

The Templers’ 12th century fortress in the Marias district of Paris, destroyed in 1808

Where the da Vinci Code leaves off

Hughes de Payns, the first Grand Master and official founder of the Knights Templar, was born near Troyes in the Champagne region of France, but if the Templars were real, the story of Lancelot, King Arthur’s knight, and the pursuit of the Holy “Grail” are pure fiction. The first person to write about them was a troubadour to the royal Court of Champagne, Chrétien de Troyes, in 1191. There is a famous basilica located in Vézelay, just 59 miles southwest of Troyes, that has long laid claim to Marie-Magdalene’s bones or “relics”.

A part of the Templar “myth” centers a supposed “holy treasure” found when Payns and his fellow monks were housed in what had once been Solomon’s Temple. In reality, all French monasteries and cathedrals at that time rivalled in the “marketing” of holy items and relics such as the bones of Saints. Saints were said to perform miracles and having a Saint’s relics was a sure calling card for pilgrims’ donations. The Templers were no exception in encouraging this sort of legend to their own profit, so it’s no wonder Dan Brown’s best selling fictional tale is set in France and not in England.

But to understand the power behind the Templar myth, we need to remember that, with the exception of monks, most people in the middle ages were illiterate. Robert de Sorbon, founder of the Sorbonne University in 1253, was a theologian and the original Sorbonne was little more than a few small houses in Paris and twenty students studying religion. All over medieval France frescos on the churches’ heavy stone walls told religious stories until the St Denis Basilica, north of Paris was built and set the stage for all the other gothic cathedrals from 1140 to 1260. After that it was the stained glass windows, for all their splendour and luminosity, that continued depicting narratives for those who couldn’t read. The glass told stories from the old and new testaments, the daily life of the craftsmen who were building the cathedrals, but also of the crusades to the Holy Land and the Templars who would participate in them. On his website Paris photographer Nhuân DôDu captures the beauty of the crusade windows in St Denis.

“Dieu le veut!”

Even before the existence of the Templars, armies of feudal knights from all over Europe had banned together in 1096 to the cry, “It’s God’s will!” and carried out the first crusade. But the knights were accompanied by unexpected hoards of ill-prepared folk intent on saving their souls by fighting their way to the Holy Land. Despite the loss of thousands of lives to famine, illness and massacre along the way, these determined masses had reconquered Jerusalem. Now, thirty years later, the tables were turned. Content to have fulfilled their pledge, most of the pilgrims had returned home to what is now Europe and the Orient had once again fallen into the hands of the Turks.

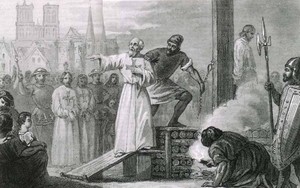

Jacques de Molay and 52 of the 15,000 Templers are burnt at the stake in 1314

Jacques de Molay and 52 of the 15,000 Templers are burnt at the stake in 1314

Still, not everyone had given up hope. Bernard de Clairvaux, an influential church leader from Champagne, had other plans. His project, launch a new crusade and Clairvaux was already busy drawing up the rules for a new Order that would help avoid the errors of the first crusade. In 1128 the future St Bernard wrote a letter to a fellow monk also from Troyes, Hughes de Payns. In his epistle, called “Elegy to the New Militia”, Bernard wrote: “A knight of Christ can cause death in total safety and die even more reassured. If he dies it’s for his own good, if he kills, it’s for Christ…” after which, together, they established the rules for the Templars. In 1145 Clairvaux would launch the second crusade from the steps of the Vézelay Basilica. Today the Ste Marie-Madeleine Basilica in Vézlay remains one of the four major starting point for the famous Chemin de Saint Jacques de Compostelle (the St James trail) to Spain.

Once the Pope officially recognized the Templers it was an easy ride. It took Hughes de Payns and his fellow monk just three years of travelling in France and Britain to muster enough wealth and logistics to set off on a second crusade. Their management skills and bravura of the Order even after Payns’ death, built an empire: fortresses in the Orient, but also monasteries called Commanderies in the form of farms with chapels all over France. Travelers through the Champagne region’s’ vast Othe forest near Troyes were subject to attacks by bandits. After the Templers, there would be a shelter every five miles. The Order issued “letters of credit” to those participating in the crusades whereby individuals could draw upon funds along the way and collect everything on their list when they arrived in the Holy Land. The movement built bridges and improved roads across France. They also planted vineyards.

The “Marais” in Paris’s third arrondissement means swamp in French. Templar monks drained the swam, planted trees and built a fortress so sturdy that it was home to the royal treasure until King St Louis moved the cache to the Louvre. The neighbourhood’s rue du Temple and alike are all references to the original Templar fortress and dungeon.

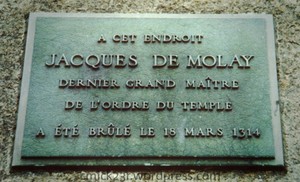

Plaque on île de la Cité in Paris where the Templar execution took place.

Plaque on île de la Cité in Paris where the Templar execution took place.

The fall

But wars, like crusades, cost money. The king of France, Philippe IV (Philippe le Bel) had become deeply in debt to the Templers in an effort to cover his own wars in the West. Moreover the Templers owed allegiance only to the Church and were becoming a threat to royal power. By the time Jacques de Molay had become Grand Master the Holy Land and its nine crusades were all officially “lost” so public support of the Order was waning. Playing upon rumours, the king, in a well devised plan, accused the Order of heresy and sodomy, forcing the Pope to condemn and eventually dissolve the Templar Order publically.

On Friday, October 13, 1307, probably the origin of the superstition surrounding Friday the 13th, all of the 2,000 Templers in France that day was arrested. The move would eventually allow Philippe to fill his coffers, giving the leftovers to the non-obtrusive Order of the Hospitaliers (later to become the Order of the Cross of Malta), lay claim to the Templar land and buildings all over France and refurbish his army with all of the knights formerly under Templar rule. Those arrested were “put to the question” until forced to confess to heresy. All but fifty-two were released, but the Grand Master Jacques de Molay and the other 51 were slowly burnt at the stake on Ile de la Cité. A plaque at the west extremity of the island still commemorates the location.

The Knights Templar today

After 1314, some of the 15,000 Templers joined the Order of the Hospitaliers, others fled south where they were welcomed by the King of Portugal and created an order in the city of Tomar, changing their name to The Order of Christ. Though they no longer officially exist today, the Order of Christ would survive for over 900 years and the city of Tomar still celebrates their memory. You can see photos of the Tomar Monastery and a commentary in English on this link.

Today in the US the Knights Templar are a part of the Masonic family. Whereas the Masonic Lodge is open to non-Christians, in the Order’s own words their goal is the “Support and Defense of the Christian Religion” and the recruiting is done primarily among “Christian” masons. Their link may be through Hughes de Payns’ founding of a Templar Order in Scotland during the group’s three year tour of France and Britain in preparation of the second crusade.

In 2001 Barbara Frale, an Italian palaeographer, happened upon the “Chinon parchment”, named after the castle where the Templers were imprisoned in the Indre-et-Loire department. The document is a letter dated 1307 found in the Vatican’s secret archives in Rome after being misfiled many centuries ago. Though the Pope gave in publically to king Philippe’s demands, the letter clearly absolves Jacques de Molay and the other members of the Order of all of the accusations of heresy. De Molay would surely have been pleased to know that somebody was on his side?

The Champagne and Burgundy regions are steeped in memories of the Templar Order, but there are traces all over France. Everywhere “rue du Temple” steets bear their name and stately buildings remind us of the immense wealth and power of the Templars at the height of their glory. The French will tell you, their true story clearly beats any best selling fiction.

Thanks to the following for permission to publish content:

More in davinci code, Knights Templar