Jimmy P. (Psychotherapy of a Plains Indian): The Talking Cure

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

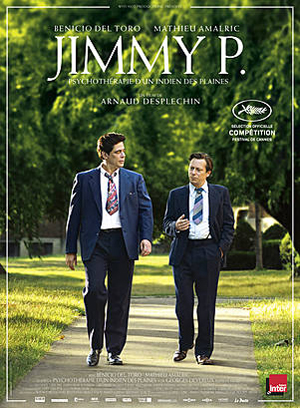

Arnaud Desplechin is one of the French cinema’s best-kept—but most highly regarded—secrets. He’s not an avant-garde director, but his challenging films (Esther Kahn, Rois et Reines, Un Conte de Noel) are firmly situated on the margins. Since his first film, Le Sentinel (which starred a mummified head) he has constantly pushed the celluloid envelope. He is revered by his cohort of film-makers as well the up-and-coming generation. With Jimmie P, he’s made his first English-language movie, set in the U.S. (though partially filmed in France). Although the movie deals with psychoanalysis, in the end it’s more about language. Leave it to Desplechin to mix Freud and Wittgenstein, with some Levi-Straus to boot.

Arnaud Desplechin is one of the French cinema’s best-kept—but most highly regarded—secrets. He’s not an avant-garde director, but his challenging films (Esther Kahn, Rois et Reines, Un Conte de Noel) are firmly situated on the margins. Since his first film, Le Sentinel (which starred a mummified head) he has constantly pushed the celluloid envelope. He is revered by his cohort of film-makers as well the up-and-coming generation. With Jimmie P, he’s made his first English-language movie, set in the U.S. (though partially filmed in France). Although the movie deals with psychoanalysis, in the end it’s more about language. Leave it to Desplechin to mix Freud and Wittgenstein, with some Levi-Straus to boot.

The film, based on a true story, is about an American Indian veteran of the Second World War suffering from strange seizures. Although he’d had a serious head injury, there doesn’t appear to be any physical reason for Jimmy’s problem. His doctors speculate that it’s psychosomatic and contact a French psychoanalyst, Georges Devereux. Devereux is interested in Amerindian culture, having spent two years in the desert learning the Mojave language. He’s a mysterious character in his own right, and seems to have been blackballed in France. We later learn that he’s not French at all, at least not originally, but from Central Europe.

In Jimmy P., Desplechin exploits classic genres for his own purposes though he doesn’t entirely escape their limitations. There’s the psychological mystery, the shrink as detective solving his patient’s problem. There’s the post-traumatic veteran film, which goes back to the Fifties, when film-makers dealt with soldiers returning from WWII. (The greatest of these is Let There Be Light, a documentary filmed by John Huston during the war, but suppressed for many years.) Jimmy P is also a buddy film in which unlike people become close friends (the relationship between Indian and Central European oddly recalls Django Unchained). There’s the plight-of-the-American-Indian exposé (Tell Them Willie Boy Is Here), though Desplechin has said that he wanted to avoid “exoticism.” There’s even a bit of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, though Desplechin’s indictment of medical care is understated.

Most of all, Desplechin stays true to his own aesthetic. He takes his time and isn’t afraid of being comprehensive—some of his previous films lasted four hours. Jimmy P is “only” two hours long, but it’s dense, with most of the film dedicated to Jimmy’s intense psychodrama. It never drags but feels long, a half-marathon of a movie. The strenuous play of characters is what interests (even obsesses) Desplechin. Some find him talky (like Jean Eustache, whose classic The Mother and the Whore probably influenced him). While as technically masterful as any director working, Desplechin doesn’t go in for pictorial effects or flashy editing. His films are as sober as his own personality.

Most of all, Desplechin stays true to his own aesthetic. He takes his time and isn’t afraid of being comprehensive—some of his previous films lasted four hours. Jimmy P is “only” two hours long, but it’s dense, with most of the film dedicated to Jimmy’s intense psychodrama. It never drags but feels long, a half-marathon of a movie. The strenuous play of characters is what interests (even obsesses) Desplechin. Some find him talky (like Jean Eustache, whose classic The Mother and the Whore probably influenced him). While as technically masterful as any director working, Desplechin doesn’t go in for pictorial effects or flashy editing. His films are as sober as his own personality.

Desplechin is lucky to have two major actors playing the principals. Benicio del Toro (Traffic, Che) as Jimmy has a monolithic presence, with a halting delivery which is painfully poignant. He manages to be expressive and sensitive through his ravaged psyche. As in many of his roles, Matthieu Almaric seems to be barely containing some demonic sort of exuberance. But here (looking remarkably like Roman Polanski) we feel something substantial concealed underneath.

The film goes astray in the middle, when Devereux is visited by his paramour Madelaine (Anne Consigny). Madelaine is from France but confusingly speaks English with a British accent (Desplechin has said he didn’t want to complicate his film with another language). Madelaine is attractive and stylish, but not charming. She’s also married, yet their supposedly passionate affair is rather low-voltage. There’s not much reason for this lust interest—she doesn’t even bring much information about Devereux’s life, except to confirm that he’s not really French. Having an attractive actress in a supporting role might have been important for commercial reasons, but detracts from the psychodrama at the film’s core.

The film goes astray in the middle, when Devereux is visited by his paramour Madelaine (Anne Consigny). Madelaine is from France but confusingly speaks English with a British accent (Desplechin has said he didn’t want to complicate his film with another language). Madelaine is attractive and stylish, but not charming. She’s also married, yet their supposedly passionate affair is rather low-voltage. There’s not much reason for this lust interest—she doesn’t even bring much information about Devereux’s life, except to confirm that he’s not really French. Having an attractive actress in a supporting role might have been important for commercial reasons, but detracts from the psychodrama at the film’s core.

After wading through a labyrinth of dreams, memories, and emotional crises, Devereux gets to the bottom of Jimmy’s mystery. Women, primal sex scenes, and sexual abuse all play a part. It’s very Freudian and very plausible. But the Amerindian element seems mislaid. We were expecting something about the intersection of American and Indian consciousness. The film does make intriguing allusions to naming and identity, to language. There are comparisons between English and Indian tongues, and between Indian languages. On Devereux’s side there’s the crossing from his Central European language (and name) to France, then to America. Devereux (and Desplechin) seem to be saying that childhood and wartime traumas are bad enough, but the Babel of mis-communication is what keeps us from dealing with them.

Jimmy P’s narrative is resolved in a sentimental way, softening the film’s tough insights. Jimmy normalizes his life, while Devereux winds up on the couch himself—now that he’s helped Jimmy the analyst is going to help himself. This is left open-ended in line with the cliché that one’s analysis is never done. Likewise, a serious film never exhausts its subject (if both film and subject are really serious). That’s why Arnaud Desplechin’s film leaves us unsatisfied but not disappointed.

Jimmy P’s narrative is resolved in a sentimental way, softening the film’s tough insights. Jimmy normalizes his life, while Devereux winds up on the couch himself—now that he’s helped Jimmy the analyst is going to help himself. This is left open-ended in line with the cliché that one’s analysis is never done. Likewise, a serious film never exhausts its subject (if both film and subject are really serious). That’s why Arnaud Desplechin’s film leaves us unsatisfied but not disappointed.

Production: Why Not Productions, Wild Bunch, France 2 Cinéma

Distribution: La Pacte

More in film review, French film, Paris films